In Nepal, Federalism, Health Policy, and the Pandemic

Published on June 10, 2020

By Dhrubaraj BK

“Without our Local Healthcare and Sanitation Act, the municipality could not have responded to the coronavirus emergency,” remarked a disaster management official in the Nepali city of Tikapur recently. Tikapur is located in the southwestern plains of Nepal, near the Indian border. As lockdowns in both countries prompted Nepali migrant workers to pick up and head for home, the municipality used its authority under this local public-health legislation to establish “health desks” at the border to provide information and health check-ups to returnees. “It has been a crucial legal instrument,” said the official.

On the other side of the country, the mayor of Damak expressed similar sentiments. “Under our municipal health policy, we used sound trucks, newspapers, and local radio to alert the public and prepare them to take precautions.”

Across Nepal, the coronavirus pandemic is confronting local governments with what may be a defining challenge to that nation’s nascent federal system. While national government instituted the nationwide lockdown, subnational governments—local governments in particular—have led the country’s public health response, providing essential information and distributing relief.

At the heart of this response have been municipalities’ Local Healthcare and Sanitation Acts.

Nepal’s 2015 constitution, hard-won after years of conflict, established a federal structure that for the first time devolved significant responsibility to newly established local governments. It designates public health as a shared responsibility: broad policy functions fall under federal or provincial jurisdiction, but primary healthcare and sanitation are exclusive functions of local government. Following landmark local elections in 2017, however, as new local leadership began to set their priorities, few focused on healthcare. Considering that Nepal has faced multiple catastrophes since 2015, including floods, landslides, fires, and the 7.8 magnitude earthquake, this was a striking omission.

To help fill this policy gap, The Asia Foundation’s Subnational Governance Program launched an initiative in cooperation with seven cities in Nepal, one from each province, including the municipalities of Tikapur, Waling, Bhimeshwar, and Damak, to assist them in developing their own Local Healthcare and Sanitation Acts. These local laws are based on powers enumerated in the constitution and national legislation. Municipalities may establish a Disaster Management Committee led by the mayor. In the event of an epidemic or other serious health hazard, the city may declare a public health emergency within their jurisdiction. A provision on emergency health services ensures that nobody will be barred from receiving emergency services at any healthcare institution within the municipality.

The Foundation first conducted a series of consultations with local officials to outline the extent of municipal powers and explore what types of legislation would best serve local needs, then developed model legislation, which each partner city adapted to fit its own circumstances. The program also developed model organizational policies and procedures to bring the healthcare laws into operation. Though barely a year has passed since these laws were adopted, they have proven to be a remarkably timely addition to the local toolkit, and the seven participating cities have shown improved capabilities in the face of the current crisis.

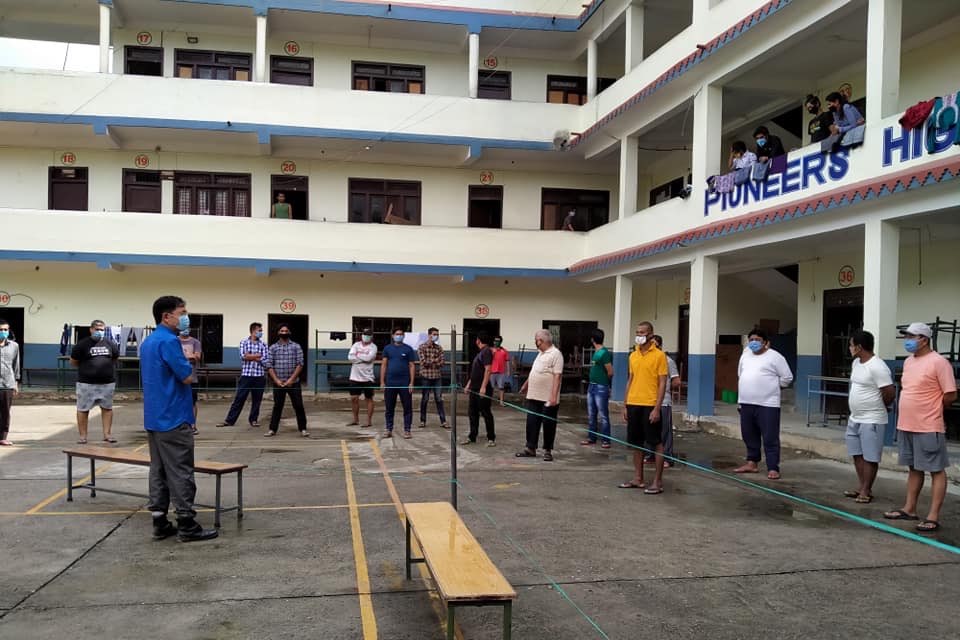

As the coronavirus began to spread in Nepal, local governments took the lead in prohibiting public gatherings, establishing information centers, setting up hand-washing systems, allocating isolation beds, and instituting quarantine procedures at public and private hospitals.

Representatives of Bhimeshwar Municipality, in the country’s central hills, visited households to gather information about people returning from abroad, counseling them to stay safely at home. “We visited the community with information about proper hand-washing and distributed soaps and masks,” said the deputy mayor.

Waling Municipality, located in the western hills, took in large numbers of returning workers and arranged quarantine protocols through community visits, despite severe shortages of personal protective equipment—masks, gloves, and scrubs. “Since we are the front line of government services to the public, we reached out to them with preparedness programs, and our municipal health policy has really been helpful as a legal guide for developing those programs,” said the mayor.

Despite these efforts, infections have continued to multiply. At the local level, newly elected representatives often lack governance expertise, and local governments have not fully developed their capacity to fulfill their responsibilities. The federal response to the crisis has also lagged, and national legislation is needed to clarify and coordinate roles and responsibilities. Many civil servants have been slow to adjust to the demands of the crisis, and resources like personal protection equipment remain in short supply. Updates from the Ministry of Health show the number of cases of Covid-19 growing by 200 a day as of June 6. With many more labor migrants expected to return from India and elsewhere abroad, this number probably has not peaked.

But if we step back and observe Nepal’s pandemic response in the broader context of the country’s still-early implementation of federalism, we can say that, on balance, local governments are proving their worth.

Originally published on asiafoundation.org. Dhrubaraj BK is a program assistant for The Asia Foundation in Nepal. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author, not those of The Asia Foundation.